John Barton Wolgamot, p.1

KEITH WALDROP on JOHN BARTON WALGAMOT

(excerpted from Part I of the interview conducted by Peter Gizzi)

(excerpted from Part I of the interview conducted by Peter Gizzi)

Peter Gizzi: Who is Wolgamot? What is the Wolgamot Society? How did it begin?

Keith Waldrop: <...> So it was the summer of '57. My brother Julian was out of prison and had started another car lot.

PG: Based on the success of the earlier one.

KW: Not in Champagne, this time, but in Danville. Danville was mainly famous for its whorehouses, but there was a bookstore run by a friend of my brother. This friend had just bought the bookstore, thinking he would make money—I think he probably went broke very soon, but he was still there then. I went through the store and found, well, a couple things I wanted. But there was this strange book. I looked at it, and couldn't make heads or tails of it. I put it back but I kept thinking about it—it was an odd shape, and I went back and looked at it again, you know, and I asked the guy who owned the shop, where did this come from? He didn't know anything about it. He had bought it, with the rest of the stock, from somebody who owned the store before him.

PG: What was the title of this book?

KW: In Sara, Mencken, Christ, and Beethoven There Were Men and Women.

[long silence]

PG: Could you repeat that?

KW: Published in 1944, it said. And the publisher's name was given as John Barton Wolgamot, same as the author's. And I think I didn't even buy it the second time. But then I ran back and got it. It was 50 cents. I became absolutely fascinated by it, and have carried it with me from then on everywhere. I never let go of it.

PG: How old were you at the time?

KW: I must have been twenty-four. And that fall I went to Michigan, so I had it with me. I used to show it to people but, you know, very special people—if I really liked them I would show them this book. And when we needed a name for a society, I think I suggested—it might have been [X. J.] Kennedy—but I thhink I said: "This is my culture hero." So we named it after him. For a while, everybody who was assumed to be a member of the Wolgamot Society, which was all our circle, was obliged to use Wolgamot's name in whatever they wrote. There were people in a particular bibliography class, for instance, and they were writing papers on everything, but always Wolgamot got into it somewhere. Everybody was quite amused that the teacher never seemed to notice. Dallas Wiebe dedicated his dissertation to Wolgamot. <...>

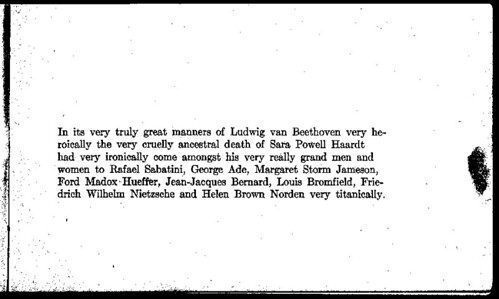

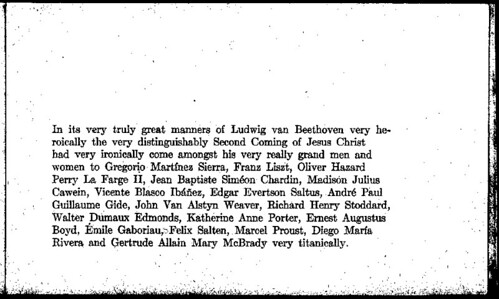

I made all sorts of weird theories about the book. One was that, since on the first page... (Well, the sentence is basically the same on every page. But there are a few odd irregularities:) ...on the first page is "the cruelly ancestral death of Sara Powell Haardt" and on the last page is the second coming of Christ. (Remember that it's called In Sara, Mencken, Christ and Beethoven There Were Men and Women—Sara is Sara Powell Haardt, who was Mencken's wife.) I said, well the plot is: Wolgamot has identified Beethoven with Mencken—Mencken wrote on Beethoven—and identifies himself, Wolgamot, with Christ. And the battle is: who will get Sara? And Mencken gets her in life, but five years after he married her she died, and Wolgamot has her in eternity.

PG: Oh, I see.

KW: So then we tried to find Wolgamot. We went through all the scholarly methods we knew anything about. I found a reference to him in the Mencken bibliography, because Mencken had willed his books to a library in Baltimore, and inside his books he had written what he thought about them. He had a copy of Wolgamot. And inside it he had written, "Wolgamot was writing this balderdash even before Sara died. I called him on the phone and I said, 'Wolgamot, are you crazy?' And he said, quite unpreturbed [sic], 'No, I'm not crazy, I just like to write that way." And from that I was even more impressed with Wolgamot.

PG: He wrote the book before she died?

KW: He started it before she died.

PG: Was she known to be sick?

KW: She was an invalid when Mencken married her. In fact, Mencken claimed the doctors had told him that she would die in a year.

I looked up book catalogs for 1944, the year Wolgamot's book came out, and I found it listed, with (since it was published privately) a place from which it could be ordered—an address in New York, down in the Village somewhere. X. J. Kennedy, in New York by chance, went by and reported a number of print shops in the building, so it could have been printed there. But when he asked around, nobody recognized the name Wolgamot. Then I found that a year before it came out, in 1943, Richard R. Smith in New York had published a book by Wolgamot, with a slightly different title, In Sara Powell Haardt Were Men and Women—close, but not the same. Richard R. Smith was a press (vanity press, I think) in New York, but by the time I found this reference, he had moved to New Hampshire or somewhere, so I got hold of the new address and wrote, simply ordering two copies of the book, as though twenty years later it would still be available. And, to my surprise he wrote back, saying there was one copy left, and I could have it for four dollars. So I bought it, and it turned out to be exactly the same book, except for the title page and the size of the margins. I got to thinking about this and again came up with an outrageous theory: that Wolgamot was working on a trilogy, and these were the first two books. The third would be the same, but with a different title page and he'd have a trilogy of great formal unity.

Finding the author seemed to be turning out a dead end. We tried everything, including asking the I Ching whether he was still alive—which gave us what seemed to be a perfectly unequivocal reply: that he was still alive, but in decline. It didn't tell us how to find him. Then I was back in Champagne-Urbana—I went to visit my mother—and saw an old friend of mine, whom I always called Zhenia (there's a poem in my first book called "For Zhenia," that's her—I wish I knew where she is now). And we were telling her about the Wolgamot Society and she said, "Oh, I know somebody named Wolgamot!" I said, "What's his first name?" And she said, "Bart." I said, "How old is he?" Well, he was twenty-two or something and was studying music at the University of Illinois. Obviously not the right person, but—we were leaving almost immediately, so I said, "You must get hold of him and ask him if John Barton Wolgamot, the author, is a relative."

Zhenia wrote soon after that she had gotten hold of him and, indeed, John Barton Wolgamot was his uncle. And, she quoted him as saying, "not my favorite one." She got from him Wolgamot's address. He was living in New York City. Along with the information that he managed a movie house. Also that he was working on another book, and that in Danville—which is apparently where his family came from, which makes sense, since that's where I found the book—there was a whole garage full of his books. We were delighted by this—after all our scholarly efforts had gone down the drain.

PG: Obviously not. You should have been a private eye.*

KW: So Kennedy and Camp were going to New York at some point, and I charged them, "Go to 104th and Broadway and find out anything you can." They came back, saying they got to the doorstep of the hotel—a run-down fleabag, according to them—and they started up the steps. But then they stopped, looked at each other, and decided no, he has to remain a legend. And they turned around and fled. The next thing that I remember, there was a party at a professor's house—actually the person who was Rosmarie's doctoral advisor, and who was on my committee too, Ingo Seidler—and the party was because Christopher Middleton was in town. I think Donald Hall was there also—he was still speaking to me at that point. And...

PG: Christopher Middleton was around then?

KW: Just passing through. His first book had come out, and Hall had gotten him a reading at Michigan. Somehow Wolgamot came up, as he tended often to do, and I said, yeah, well, we've found his phone number (how could one forget Monument six one thousand?), and Seidler immediately put the phone by me and said, "Call him. Invite him to come and read." The Wolgamot Society had made a little money because of Ubu Roi. (Never made money on anything else.) So, put to it, I called person-to-person and I heard the answer, this is hotel whatever-it-was-called, and the operator said, "There's a call for Mr. John Wolgamot." And I heard the hotel clerk—"Wolgamot? Is it paid for?" And the operator said, yes it was paid for, and so Wolgamot came on the line.

I hadn't realized how late it was—we had awakened him—and I asked him if he would come read his work at the University of Michigan, and he said, "Work? What work?" I said In Sara, Mencken, Christ and Beethoven There Were Men and Women. He said, "Ohhhh" and then he said, "I thought that book had died the death." I assured him that at the University of Michigan there were many people very interested in it, and we'd like to hear him read it. But he said, well no he could't do that, because he worked for an organization that wouldn't want to do without him that long. We later found that he didn't believe in readings. That was the call, and it was unsuccessful, but I had talked to him.

I've often felt that I haven't done enough for Wolgamot's reputation—Kennedy and I thought at one time of putting out a new edition with index and with notes on all the names in it, to the extent that we could identify them, but we never did it.

Soon after I came to Providence, Robert Ashley wrote that he had left Michigan and gone to Mills College, where he had spent years building an electronic studio; and he had written no music for years because—his letter said—he had been purifying himself. Now, he said, "I am pure." And ready to write his masterpiece. The only thing was, the one text he had to have was lacking. The work could only be based on Wolgamot. And he said—I was impressed by the humility in this—he said he knew I wouldn't let the book out of my hands, but if I could Xerox a couple pages<...>

So when Ashley wrote, I had that copy to send him. His composition was premiered at the Bremen festival. Then he performed it up and down the west coast, but he wanted to play it in New York. And he thought, but I never told Wolgamot! Then in Los Angeles, I think—somewhere in southern California, anyway—before a performance, a woman appeared and said, "I noticed the title of your composition In Sara, Mencken, Christ and Beethoven There Were Men and Women. Does this composition have something to do with John Barton Wolgamot?"

And he said, "uh, uh, well, uh... yes." And she introduced herself to him saying that she had for years been Wolgamot's "only confidante," including the very time he was writing his book. But she had seen him recently, and asked Ashley. "Have you told Wolgamot about this?" and he said, well, no, he hadn't yet. She said. "Well, you know, I think he must have some idea of it, because I saw him recently in New York, and I think, after years of self-imposed obscurity, he's ready for a little fame. When I talked to him he said he thought there was something in the wind."

PG: Because of your phone call?

KW: Oh, this was years after the phone call. And she said, "You must get in touch with him." Then she was leaving, but just before she left she said, "Oh, by the way—you'd better bone up on the Eroica." And went out. Ashley was nervous. He had no idea what Beethoven could have to do with it! He gave me a frantic call, just a bit later, because he had gotten in contact with Wolgamot, and had made an appointment to see him. And, he said, "I can't go alone!" So I said, "All right, I'll come to New York and go with you."

Well, I cut it a little close and the train was an hour late, and when I got to the movie-house—the Little Carnegie, where Wolgamot was the manager and where he had consented to be interviewed—Ashley was already there, and the first thing Wolgamot had said to him was, "Are you the person who called me in the middle of the night ten years ago?" And Ashley said, "Oh no, no no—that was Keith Waldrop!"

Ashley had done a formal analysis of the book, and I had made an elaborate chart, claiming that the book is in four movements—there was no sign of this, no markings—of equal length. I thought, well, it helps him in composing his piece, but probably has nothing to do with it. But the first thing I remember Wolgamot saying was, "You realize, this is in four movements." And Ashley immediately brought out his chart, at which Wolgamot simply turned his head—he wouldn't look at it. And he wouldn't listen to the piece, by the way, he didn't want to hear it.

He said his book was based on the four movements of the Eroica Symphony. He said that in 1938 or '39—around there—he heard the Eroica for the first time, and he was bowled over by it. He realized instantly that this was the work that did everything, said everything, this was the master work of all time, this had everything. He also realized, he said, that it was great because of the rhythm.

And as he listened to it, he kept hearing names. And he wrote down the names—he said they were names he didn't know, that didn't mean anything to him—but he wrote them down as he heard them. Then he went to a biography of Beethoven—this is what he claimed—he went to a biography of Beethoven, and he said he found all those names.

PG: Wow.

KW: And he realized, after thinking about this, that rhythm is the basis of everything, and names are the basis of rhythm. He said that's why, when a woman gets married and changes her name, she loses her character. He said, "You know, you can even hear this in the name of fictional characters. For instance, Anna Karenina: listen to that—ann-a-ka-ren-in-a ann-a-ka-ren-in-a—it's the railroad: that's why she gets run over by a train." And Ashley all this time was sinking deeper in his chair.

What else? Let's see.

I said, "Are you working on another book?" And he said yes, yes, he'd been working on another books since his second book came out. He said, "My first book was no good. My second book began to gallop. But you haven't seen anything yet." The third one, he'd been working on since 194, in other words for thirty years. He said, writing took longer now because he had to work. At the time he wrote the first two books, he didn't have to work and could spend all his time on them. Now his money had run out and he had to work. And I said, Now your next book—the first two books I had, which were, you remember, exactly the same text—I said, "Well, the text of the third book—is that going to be..." And he said, as if it went without saying, "Oh, same text, same text."

PG: Amazing—30 years on a single line.

KW: He had been working on: the title, the title page, the size of the margins.

I asked him, "Did you ever meet Mencken?" He said, "No, I never met Mencken. I talked to him on the phone once," which I already knew. I said, "Well, then, you probably never met Sara Powell Haardt." I could see Ashley was remembering my silly theory. And Wolgamot said, "No, I never met Sara Powell Haardt. I used her name, because her last name's Haardt and my middle name's Bart." I thought, well that shoots my theory. But he went on, "Of course, in the book, I represent myself as having an illicit relation with her. In a book like this, there has to be some love interest." I thought Ashley would go clean through his chair!

PG: The illicit love interest according to your theory happens in the afterlife—in eternity.

KW: Yes. But, after all, an eternity inside his book.

I kept telling him, I'm a printer. What about the third book? He said it wasn't done yet, but he never responded to the fact that I was a printer. He said that his third book, he thought probably should be published by a commercial press. I thought—whew.

Then he said, "Do you know anything about October House?" I said, well, I had a friend who published a book with them. He said, "It's not a communist front, is it?" I said, no, I was sure it wasn't. And besides, I thought it didn't actually exist anymore. This made me realize that he knew nothing about it, so I said, "What made you light on October House?" He said, well, it was perfectly obvious. "October's the tenth month, but it means eight. And 'house' has five letters. 1805—that's the year of the Eroica!"

PG: He's truly mad.

KW: Ashley was in seventh heaven. Ashley has a thing about naive artists. And he had decided, from the book, that this was the Great Naive Artist, and now...

PG: The recording's nice, because he cut out all the breaths so that it has this quality...

KW: Yes, Ashley first read the entire book onto a tape, breathing only between pages, then went back and, as you say, cut out all the breaths. Which reminds me: when Wolgamot heard that in Bob's composition the text was actually spoken, he said that at one time he had thought of reading it out loud. "But then I decided against it," he said. "I suppose that—if you did read it—it would have to be a kind of, well, breathless reading." <...>

PG: So, there's one more part of the story that when he died you went to look into the safety-deposit box to see...

KW: Ashley tried to keep in touch with him, which became more and more difficult. He did visit Ashley, and Ashley him. In fact, he once took Ashley and Mimi Johnson to the Russian Tea Room. But later the Little Carnegie was torn down, and he started working for a different movie house, somewhere in the suburbs I think, and—rather all of a sudden—stopped being sociable. And so it was a great surprise that, when Wolgamot died, in his will he had appointed Ashley his literary executor. Ashley was supposed to receive the contents of this famous safety-deposit box, which we assumed would be the plates for the book—because Wolgamot had told us he still had the plates. After some legal folderol, the contents of the box were delivered to Ashley, but all that was in the box was a metal stamp—the kind of thing you stamp a book cover with. It was for the new title, the title for his third book. Its title is Beacons of Ancestorship.

PG: That would have been the trilogy, so you actually have it.

KW: Exactly.

PG: You could print it as a trilogy.

KW: Well, I think we'll just print one book, the third. We've been intending to do an edition of it. And hoping to put another volume with it, which would contain my anecdotal history of these things and also Ashley's analysis of the book. <...>

Actually I haven't mentioned the way he wrote the book.

PG: That's important.

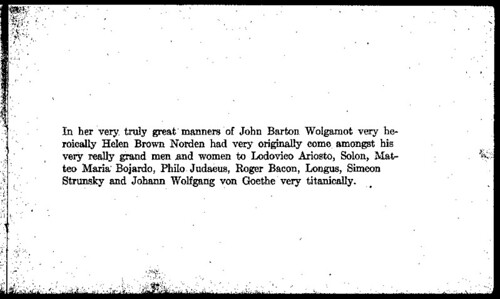

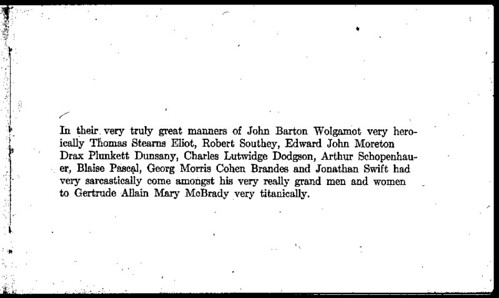

KW: When he realized that names were the basis of everything, he decided that all you'd have to do is write names, and that'd be it. So he wrote a name, and then on another page he wrote another name and so forth (in four movements). He soon realized that wasn't quite enough—you had to have different names to play off each other, to make a more complex rhythm. So he put together big lists of names, mostly of writers. He said, "I didn't read all these authors, but they're all good authors." And some artists, musicians and so forth. He had big lists, and he claimed that to the one name on a page he'd put these other names up next to it and "when there was a real spark between them," he would know those names went together. So then he had three names on a page. And then he collected other names around each of these three, and he said that then he knew it really was perfect. It was all it needed to be—each page was perfect—except that there was no reason to turn the page. He knew he had to have a sentence, only one sentence. That one sentence would be on every page. He claimed that's what took him so long. All the rest he did fairly fast, but it took him ten years to write that one sentence. He said that it was so difficult "because, you know, it's very hard to find a sentence that doesn't say anything."

_________

* Since this interview was conducted, a French philosopher, reviewing the pamphlet John Barton Wolgamot, translation by Marcel Cohen of an improvised account of the search for Wolgamot, has written: "Le livre de K. Waldrop est une enquête policière..." Alain Chareyre-Méjan, "L'Ecrivain, le Cancre, le Privé" in La Licorne (1998).

Keith Waldrop: <...> So it was the summer of '57. My brother Julian was out of prison and had started another car lot.

PG: Based on the success of the earlier one.

KW: Not in Champagne, this time, but in Danville. Danville was mainly famous for its whorehouses, but there was a bookstore run by a friend of my brother. This friend had just bought the bookstore, thinking he would make money—I think he probably went broke very soon, but he was still there then. I went through the store and found, well, a couple things I wanted. But there was this strange book. I looked at it, and couldn't make heads or tails of it. I put it back but I kept thinking about it—it was an odd shape, and I went back and looked at it again, you know, and I asked the guy who owned the shop, where did this come from? He didn't know anything about it. He had bought it, with the rest of the stock, from somebody who owned the store before him.

PG: What was the title of this book?

KW: In Sara, Mencken, Christ, and Beethoven There Were Men and Women.

[long silence]

PG: Could you repeat that?

KW: Published in 1944, it said. And the publisher's name was given as John Barton Wolgamot, same as the author's. And I think I didn't even buy it the second time. But then I ran back and got it. It was 50 cents. I became absolutely fascinated by it, and have carried it with me from then on everywhere. I never let go of it.

PG: How old were you at the time?

KW: I must have been twenty-four. And that fall I went to Michigan, so I had it with me. I used to show it to people but, you know, very special people—if I really liked them I would show them this book. And when we needed a name for a society, I think I suggested—it might have been [X. J.] Kennedy—but I thhink I said: "This is my culture hero." So we named it after him. For a while, everybody who was assumed to be a member of the Wolgamot Society, which was all our circle, was obliged to use Wolgamot's name in whatever they wrote. There were people in a particular bibliography class, for instance, and they were writing papers on everything, but always Wolgamot got into it somewhere. Everybody was quite amused that the teacher never seemed to notice. Dallas Wiebe dedicated his dissertation to Wolgamot. <...>

I made all sorts of weird theories about the book. One was that, since on the first page... (Well, the sentence is basically the same on every page. But there are a few odd irregularities:) ...on the first page is "the cruelly ancestral death of Sara Powell Haardt" and on the last page is the second coming of Christ. (Remember that it's called In Sara, Mencken, Christ and Beethoven There Were Men and Women—Sara is Sara Powell Haardt, who was Mencken's wife.) I said, well the plot is: Wolgamot has identified Beethoven with Mencken—Mencken wrote on Beethoven—and identifies himself, Wolgamot, with Christ. And the battle is: who will get Sara? And Mencken gets her in life, but five years after he married her she died, and Wolgamot has her in eternity.

PG: Oh, I see.

KW: So then we tried to find Wolgamot. We went through all the scholarly methods we knew anything about. I found a reference to him in the Mencken bibliography, because Mencken had willed his books to a library in Baltimore, and inside his books he had written what he thought about them. He had a copy of Wolgamot. And inside it he had written, "Wolgamot was writing this balderdash even before Sara died. I called him on the phone and I said, 'Wolgamot, are you crazy?' And he said, quite unpreturbed [sic], 'No, I'm not crazy, I just like to write that way." And from that I was even more impressed with Wolgamot.

PG: He wrote the book before she died?

KW: He started it before she died.

PG: Was she known to be sick?

KW: She was an invalid when Mencken married her. In fact, Mencken claimed the doctors had told him that she would die in a year.

I looked up book catalogs for 1944, the year Wolgamot's book came out, and I found it listed, with (since it was published privately) a place from which it could be ordered—an address in New York, down in the Village somewhere. X. J. Kennedy, in New York by chance, went by and reported a number of print shops in the building, so it could have been printed there. But when he asked around, nobody recognized the name Wolgamot. Then I found that a year before it came out, in 1943, Richard R. Smith in New York had published a book by Wolgamot, with a slightly different title, In Sara Powell Haardt Were Men and Women—close, but not the same. Richard R. Smith was a press (vanity press, I think) in New York, but by the time I found this reference, he had moved to New Hampshire or somewhere, so I got hold of the new address and wrote, simply ordering two copies of the book, as though twenty years later it would still be available. And, to my surprise he wrote back, saying there was one copy left, and I could have it for four dollars. So I bought it, and it turned out to be exactly the same book, except for the title page and the size of the margins. I got to thinking about this and again came up with an outrageous theory: that Wolgamot was working on a trilogy, and these were the first two books. The third would be the same, but with a different title page and he'd have a trilogy of great formal unity.

Finding the author seemed to be turning out a dead end. We tried everything, including asking the I Ching whether he was still alive—which gave us what seemed to be a perfectly unequivocal reply: that he was still alive, but in decline. It didn't tell us how to find him. Then I was back in Champagne-Urbana—I went to visit my mother—and saw an old friend of mine, whom I always called Zhenia (there's a poem in my first book called "For Zhenia," that's her—I wish I knew where she is now). And we were telling her about the Wolgamot Society and she said, "Oh, I know somebody named Wolgamot!" I said, "What's his first name?" And she said, "Bart." I said, "How old is he?" Well, he was twenty-two or something and was studying music at the University of Illinois. Obviously not the right person, but—we were leaving almost immediately, so I said, "You must get hold of him and ask him if John Barton Wolgamot, the author, is a relative."

Zhenia wrote soon after that she had gotten hold of him and, indeed, John Barton Wolgamot was his uncle. And, she quoted him as saying, "not my favorite one." She got from him Wolgamot's address. He was living in New York City. Along with the information that he managed a movie house. Also that he was working on another book, and that in Danville—which is apparently where his family came from, which makes sense, since that's where I found the book—there was a whole garage full of his books. We were delighted by this—after all our scholarly efforts had gone down the drain.

PG: Obviously not. You should have been a private eye.*

KW: So Kennedy and Camp were going to New York at some point, and I charged them, "Go to 104th and Broadway and find out anything you can." They came back, saying they got to the doorstep of the hotel—a run-down fleabag, according to them—and they started up the steps. But then they stopped, looked at each other, and decided no, he has to remain a legend. And they turned around and fled. The next thing that I remember, there was a party at a professor's house—actually the person who was Rosmarie's doctoral advisor, and who was on my committee too, Ingo Seidler—and the party was because Christopher Middleton was in town. I think Donald Hall was there also—he was still speaking to me at that point. And...

PG: Christopher Middleton was around then?

KW: Just passing through. His first book had come out, and Hall had gotten him a reading at Michigan. Somehow Wolgamot came up, as he tended often to do, and I said, yeah, well, we've found his phone number (how could one forget Monument six one thousand?), and Seidler immediately put the phone by me and said, "Call him. Invite him to come and read." The Wolgamot Society had made a little money because of Ubu Roi. (Never made money on anything else.) So, put to it, I called person-to-person and I heard the answer, this is hotel whatever-it-was-called, and the operator said, "There's a call for Mr. John Wolgamot." And I heard the hotel clerk—"Wolgamot? Is it paid for?" And the operator said, yes it was paid for, and so Wolgamot came on the line.

I hadn't realized how late it was—we had awakened him—and I asked him if he would come read his work at the University of Michigan, and he said, "Work? What work?" I said In Sara, Mencken, Christ and Beethoven There Were Men and Women. He said, "Ohhhh" and then he said, "I thought that book had died the death." I assured him that at the University of Michigan there were many people very interested in it, and we'd like to hear him read it. But he said, well no he could't do that, because he worked for an organization that wouldn't want to do without him that long. We later found that he didn't believe in readings. That was the call, and it was unsuccessful, but I had talked to him.

I've often felt that I haven't done enough for Wolgamot's reputation—Kennedy and I thought at one time of putting out a new edition with index and with notes on all the names in it, to the extent that we could identify them, but we never did it.

Soon after I came to Providence, Robert Ashley wrote that he had left Michigan and gone to Mills College, where he had spent years building an electronic studio; and he had written no music for years because—his letter said—he had been purifying himself. Now, he said, "I am pure." And ready to write his masterpiece. The only thing was, the one text he had to have was lacking. The work could only be based on Wolgamot. And he said—I was impressed by the humility in this—he said he knew I wouldn't let the book out of my hands, but if I could Xerox a couple pages<...>

So when Ashley wrote, I had that copy to send him. His composition was premiered at the Bremen festival. Then he performed it up and down the west coast, but he wanted to play it in New York. And he thought, but I never told Wolgamot! Then in Los Angeles, I think—somewhere in southern California, anyway—before a performance, a woman appeared and said, "I noticed the title of your composition In Sara, Mencken, Christ and Beethoven There Were Men and Women. Does this composition have something to do with John Barton Wolgamot?"

And he said, "uh, uh, well, uh... yes." And she introduced herself to him saying that she had for years been Wolgamot's "only confidante," including the very time he was writing his book. But she had seen him recently, and asked Ashley. "Have you told Wolgamot about this?" and he said, well, no, he hadn't yet. She said. "Well, you know, I think he must have some idea of it, because I saw him recently in New York, and I think, after years of self-imposed obscurity, he's ready for a little fame. When I talked to him he said he thought there was something in the wind."

PG: Because of your phone call?

KW: Oh, this was years after the phone call. And she said, "You must get in touch with him." Then she was leaving, but just before she left she said, "Oh, by the way—you'd better bone up on the Eroica." And went out. Ashley was nervous. He had no idea what Beethoven could have to do with it! He gave me a frantic call, just a bit later, because he had gotten in contact with Wolgamot, and had made an appointment to see him. And, he said, "I can't go alone!" So I said, "All right, I'll come to New York and go with you."

Well, I cut it a little close and the train was an hour late, and when I got to the movie-house—the Little Carnegie, where Wolgamot was the manager and where he had consented to be interviewed—Ashley was already there, and the first thing Wolgamot had said to him was, "Are you the person who called me in the middle of the night ten years ago?" And Ashley said, "Oh no, no no—that was Keith Waldrop!"

Ashley had done a formal analysis of the book, and I had made an elaborate chart, claiming that the book is in four movements—there was no sign of this, no markings—of equal length. I thought, well, it helps him in composing his piece, but probably has nothing to do with it. But the first thing I remember Wolgamot saying was, "You realize, this is in four movements." And Ashley immediately brought out his chart, at which Wolgamot simply turned his head—he wouldn't look at it. And he wouldn't listen to the piece, by the way, he didn't want to hear it.

He said his book was based on the four movements of the Eroica Symphony. He said that in 1938 or '39—around there—he heard the Eroica for the first time, and he was bowled over by it. He realized instantly that this was the work that did everything, said everything, this was the master work of all time, this had everything. He also realized, he said, that it was great because of the rhythm.

And as he listened to it, he kept hearing names. And he wrote down the names—he said they were names he didn't know, that didn't mean anything to him—but he wrote them down as he heard them. Then he went to a biography of Beethoven—this is what he claimed—he went to a biography of Beethoven, and he said he found all those names.

PG: Wow.

KW: And he realized, after thinking about this, that rhythm is the basis of everything, and names are the basis of rhythm. He said that's why, when a woman gets married and changes her name, she loses her character. He said, "You know, you can even hear this in the name of fictional characters. For instance, Anna Karenina: listen to that—ann-a-ka-ren-in-a ann-a-ka-ren-in-a—it's the railroad: that's why she gets run over by a train." And Ashley all this time was sinking deeper in his chair.

What else? Let's see.

I said, "Are you working on another book?" And he said yes, yes, he'd been working on another books since his second book came out. He said, "My first book was no good. My second book began to gallop. But you haven't seen anything yet." The third one, he'd been working on since 194, in other words for thirty years. He said, writing took longer now because he had to work. At the time he wrote the first two books, he didn't have to work and could spend all his time on them. Now his money had run out and he had to work. And I said, Now your next book—the first two books I had, which were, you remember, exactly the same text—I said, "Well, the text of the third book—is that going to be..." And he said, as if it went without saying, "Oh, same text, same text."

PG: Amazing—30 years on a single line.

KW: He had been working on: the title, the title page, the size of the margins.

I asked him, "Did you ever meet Mencken?" He said, "No, I never met Mencken. I talked to him on the phone once," which I already knew. I said, "Well, then, you probably never met Sara Powell Haardt." I could see Ashley was remembering my silly theory. And Wolgamot said, "No, I never met Sara Powell Haardt. I used her name, because her last name's Haardt and my middle name's Bart." I thought, well that shoots my theory. But he went on, "Of course, in the book, I represent myself as having an illicit relation with her. In a book like this, there has to be some love interest." I thought Ashley would go clean through his chair!

PG: The illicit love interest according to your theory happens in the afterlife—in eternity.

KW: Yes. But, after all, an eternity inside his book.

I kept telling him, I'm a printer. What about the third book? He said it wasn't done yet, but he never responded to the fact that I was a printer. He said that his third book, he thought probably should be published by a commercial press. I thought—whew.

Then he said, "Do you know anything about October House?" I said, well, I had a friend who published a book with them. He said, "It's not a communist front, is it?" I said, no, I was sure it wasn't. And besides, I thought it didn't actually exist anymore. This made me realize that he knew nothing about it, so I said, "What made you light on October House?" He said, well, it was perfectly obvious. "October's the tenth month, but it means eight. And 'house' has five letters. 1805—that's the year of the Eroica!"

PG: He's truly mad.

KW: Ashley was in seventh heaven. Ashley has a thing about naive artists. And he had decided, from the book, that this was the Great Naive Artist, and now...

PG: The recording's nice, because he cut out all the breaths so that it has this quality...

KW: Yes, Ashley first read the entire book onto a tape, breathing only between pages, then went back and, as you say, cut out all the breaths. Which reminds me: when Wolgamot heard that in Bob's composition the text was actually spoken, he said that at one time he had thought of reading it out loud. "But then I decided against it," he said. "I suppose that—if you did read it—it would have to be a kind of, well, breathless reading." <...>

PG: So, there's one more part of the story that when he died you went to look into the safety-deposit box to see...

KW: Ashley tried to keep in touch with him, which became more and more difficult. He did visit Ashley, and Ashley him. In fact, he once took Ashley and Mimi Johnson to the Russian Tea Room. But later the Little Carnegie was torn down, and he started working for a different movie house, somewhere in the suburbs I think, and—rather all of a sudden—stopped being sociable. And so it was a great surprise that, when Wolgamot died, in his will he had appointed Ashley his literary executor. Ashley was supposed to receive the contents of this famous safety-deposit box, which we assumed would be the plates for the book—because Wolgamot had told us he still had the plates. After some legal folderol, the contents of the box were delivered to Ashley, but all that was in the box was a metal stamp—the kind of thing you stamp a book cover with. It was for the new title, the title for his third book. Its title is Beacons of Ancestorship.

PG: That would have been the trilogy, so you actually have it.

KW: Exactly.

PG: You could print it as a trilogy.

KW: Well, I think we'll just print one book, the third. We've been intending to do an edition of it. And hoping to put another volume with it, which would contain my anecdotal history of these things and also Ashley's analysis of the book. <...>

Actually I haven't mentioned the way he wrote the book.

PG: That's important.

KW: When he realized that names were the basis of everything, he decided that all you'd have to do is write names, and that'd be it. So he wrote a name, and then on another page he wrote another name and so forth (in four movements). He soon realized that wasn't quite enough—you had to have different names to play off each other, to make a more complex rhythm. So he put together big lists of names, mostly of writers. He said, "I didn't read all these authors, but they're all good authors." And some artists, musicians and so forth. He had big lists, and he claimed that to the one name on a page he'd put these other names up next to it and "when there was a real spark between them," he would know those names went together. So then he had three names on a page. And then he collected other names around each of these three, and he said that then he knew it really was perfect. It was all it needed to be—each page was perfect—except that there was no reason to turn the page. He knew he had to have a sentence, only one sentence. That one sentence would be on every page. He claimed that's what took him so long. All the rest he did fairly fast, but it took him ten years to write that one sentence. He said that it was so difficult "because, you know, it's very hard to find a sentence that doesn't say anything."

_________

* Since this interview was conducted, a French philosopher, reviewing the pamphlet John Barton Wolgamot, translation by Marcel Cohen of an improvised account of the search for Wolgamot, has written: "Le livre de K. Waldrop est une enquête policière..." Alain Chareyre-Méjan, "L'Ecrivain, le Cancre, le Privé" in La Licorne (1998).